The Witches

There are nights when I look at myself in the mirror and it feels like I’m not alone.

Someone else is standing there with me—

a tall, lacquered silhouette from 1990,

a woman who terrified an entire generation in a velvet hat and a slash of red lipstick.

Angelica Huston’s Grand High Witch, also known as Eva Ernst.

I don’t mean the actress.

I mean the apparition she played:

all precision, all poise, all venomous glamour, a kind of feminine severity that refuses to soften itself for anyone.

As a child, I didn’t know why I recognized her.

As an adult, I do.

She is what happens when a woman knows exactly what she is and refuses to pretend otherwise.

Tonight, dressing in the studio, I felt her arrive before I even reached for the hat.

The lace gloves.

The structure of the black dress.

The veiled brim pulled low enough to obscure the eyes.

The boots that shift your entire posture by a single inch of authority.

I wasn’t imitating her.

I was remembering a language I’ve always known—

the grammar of severe elegance, the syntax of withheld softness,

the dialect spoken by women who have learned to walk into a room without apology.

And when I caught my reflection—the straight spine, the red mouth, the unblinking stare—I felt it all over again:

not performance, but permission.

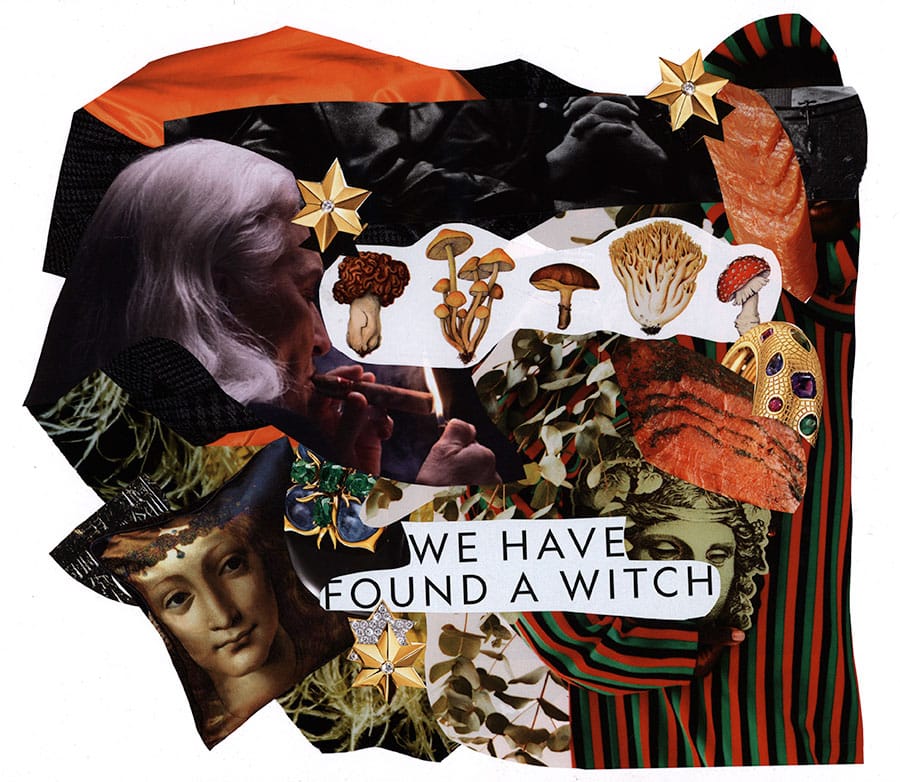

The studio transformed behind me: racks of dresses, wigs on mannequin heads, gloves draped like relics.

A coven in storage.

An archive of former selves.

Every piece of cloth whispering some instruction about who I’m allowed to be.

In that moment, I wasn’t dressing up.

I was calling something forward.

People love to say the Grand High Witch is terrifying because she takes her face off.

But what terrified me as a child wasn’t the creature beneath the glamour—

it was how convincingly she wore the glamour in the first place.

How she wielded beauty like a blade.

How she inhabited the mask so fully that removing it felt like a decision, not a revelation.

When cancer made me bald, I thought of her constantly.

Not because I felt monstrous—

but because I felt unveiled.

There is a particular clarity that arrives when there is nothing left to hide behind.

A new kind of truth-telling.

A power that doesn’t depend on illusion.

I felt more honest without hair than I ever did with it.

That was the first time I understood the Grand High Witch not as a villain,

but as a woman unmasked by circumstance,

claiming whatever remained.

But there is another seam in this identification—

one I didn’t have language for until recently.

The Grand High Witch hates children.

She destroys them.

Her entire cosmology is built on eliminating the thing she cannot make.

As a girl, I felt a strange jolt watching that.

Not fear—

a kind of terrible recognition.

Even then I sensed that motherhood might never be available to me.

Not because I didn’t want it,

but because it might not be possible.

A door my body would never open.

And now, after everything—illness, treatment, survival, the years of managing a body that has been burned clean and rebuilt—I know that the likelihood of conceiving is almost nonexistent.

A truth that sits in my life quietly, but heavily.

So when people insist the witch’s hatred is simple cruelty, I flinch.

I know the deeper script:

the way culture punishes a woman who cannot (or will not) give the world the child it believes redeems her.

The way barren or infertile femininity is framed as monstrous.

The way women outside reproductive destiny are cast as threats.

In the film, a woman who cannot create life becomes one who destroys it.

This is how mythology disciplines female power:

if you do not nurture, you must be dangerous.

But tonight, slipping the veil over my face, I felt the truth shift.

The Grand High Witch doesn’t hate children.

She hates the expectations that were written for her body.

She hates the destiny assigned without consent.

She hates the narrow corridor she was forced into.

What she destroys is not innocence—

it’s the script.

When I stood in front of the mirror in the studio—gloves on, brim casting shadow, the whole silhouette sharpened into something almost ceremonial—I realized I wasn’t invoking her.

I was inheriting her.

Not her cruelty.

Not her villainy.

But her sovereignty.

Her refusal to be softened.

Her authorship of self in a world that demands women be legible, maternal, comforting, harmless.

I understand now why she frightened everyone in that hotel ballroom:

she was too much woman for the frame.

Too powerful, too precise, too unapologetic.

Tonight, I stepped into that lineage fully.

Not as an imitation, but as a continuation—

a reminder that the monstrous and the magnificent have always been mine to choose from,

and that the story of my body—bald, scarred, powerful, unbeholden—

is not a tragedy but a spell.

One I get to cast.

One I get to rewrite.

One I no longer hide.