EPB Style Lab No. 2: Service Garment / Sacred Garment

✧ Not in Uniform

This isn’t a uniform. Not anymore.

It’s a relic—gifted, storied, worn in a place it was never meant to land.

The Singapore Airlines sarong kebaya, designed by Pierre Balmain in 1968, was never just fabric. It was brand architecture, colonial residue, gender performance, and cultural compression sewn into a single silhouette.

I didn’t wear it in service. I wore it in Brooklyn, decades later, on a rooftop. Not to fly—but to haunt.

✧ Pierre Balmain’s Discipline

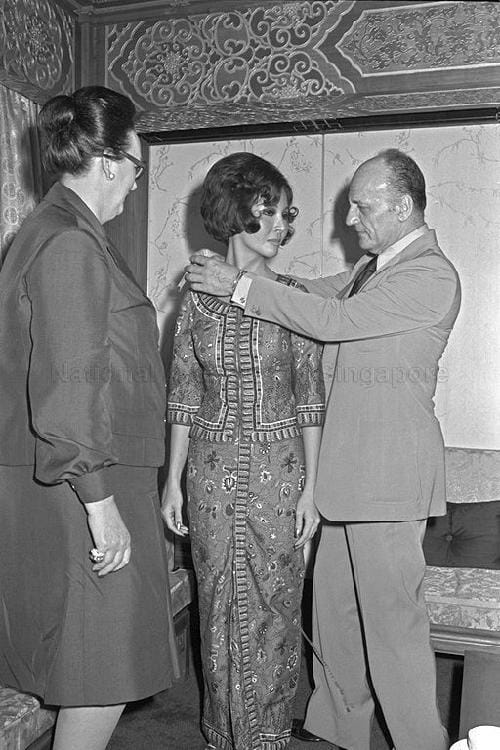

Balmain’s design was a fusion of haute couture precision and cultural symbolism—tight tailoring from French hands wrapped around Southeast Asian batik.

The kebaya came to embody soft power: demure, elegant, always smiling.

Crew members underwent multiple fittings. The neckline was regulated. The hem calibrated. Even the fabric spoke of containment.

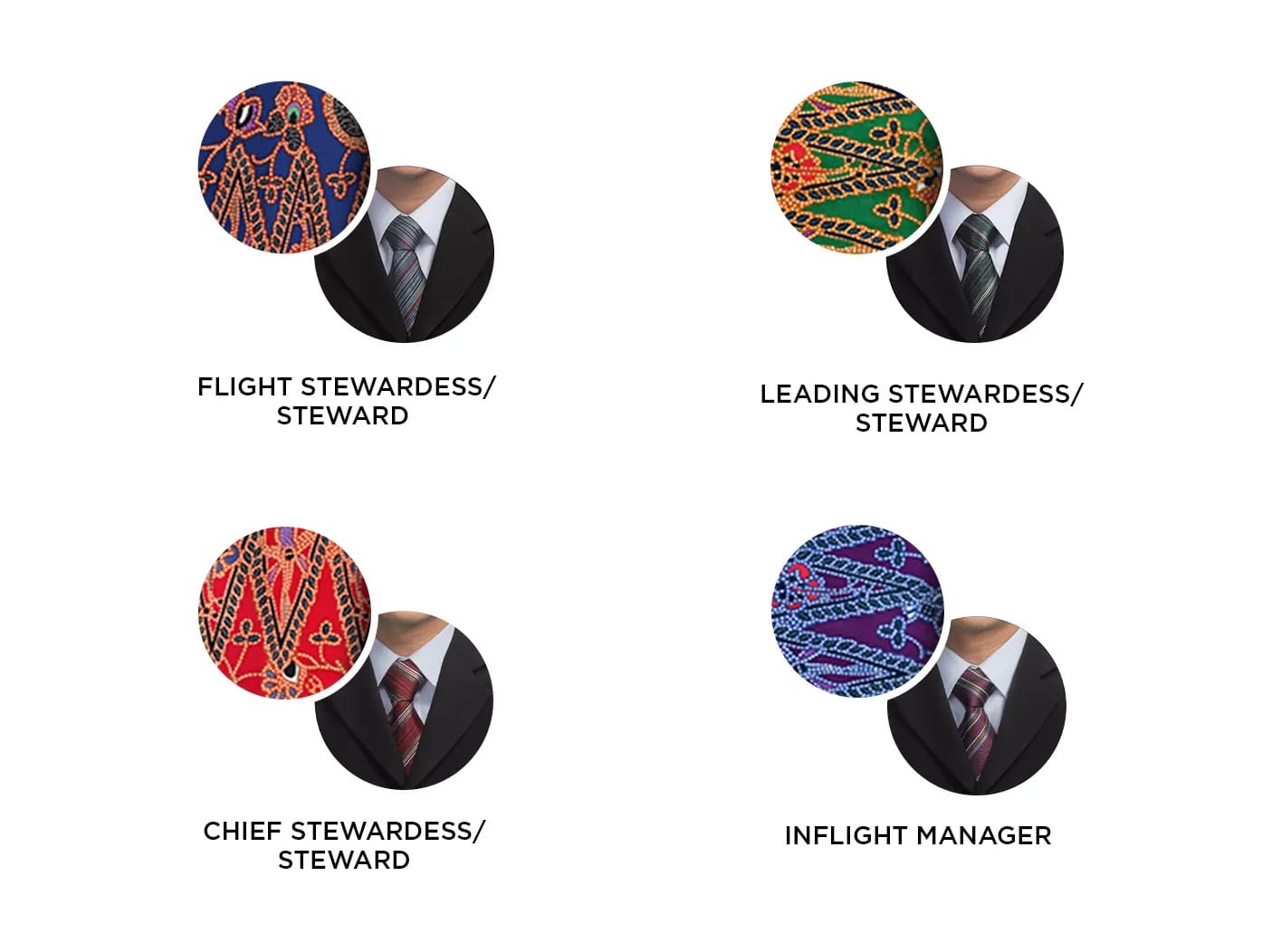

Balmain designed the SIA uniform in four colors, coded by rank:

- Blue: Stewardess

- Green: Leading Stewardess

- Red: Chief Stewardess

- Purple: In-flight Supervisor

Mine is blue. The entry point of a hierarchy I never joined.

It now reads less like a rank, more like a memory.

✧ The Style Lab Method: Rethread and Rearrange

EPB Style Lab doesn’t preserve garments. It disrupts them.

Uniforms are treated like collage: disassembled, reinterpreted, destabilized.

The kebaya doesn’t function here as nostalgia. It becomes strategy. Aesthetic residue. Embodied critique.

What was once costume becomes material archive.

What once promised compliance now offers its threads to another story.

The gift from Serin, the stewardess that was so kind to me for the 18 hour non stop flight from JFK to SGA —unexpected, precise—catalyzed this reworking.

To wear it is to both honor and interrupt.

✧ The Afterlife of Uniform

The kebaya was never just fabric. It carried discipline, fantasy, labor—cut to fit a brand of femininity.

Now it circulates again: unfastened from service, reworn without instruction.

Not to reenact, but to rearrange. Not as homage, but as interruption.